Back Eleccions legislatives russes de 2011 Catalan Parlamentní volby v Rusku 2011 Czech Ruslands parlamentsvalg 2011 Danish Parlamentswahl in Russland 2011 German Elecciones legislativas de Rusia de 2011 Spanish 2011. aasta Venemaa parlamendivalimised Estonian Venäjän duuman vaalit 2011 Finnish Élections législatives russes de 2011 French Eleccións lexislativas de Rusia de 2011 Galician הבחירות הפרלמנטריות ברוסיה 2011 HE

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 450 seats in the State Duma 226 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 60.10% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This lists parties that won seats. See the complete results below.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

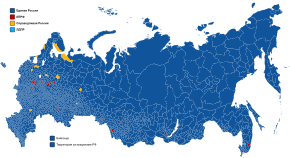

Legislative elections were held in Russia on 4 December 2011.[1] At stake were the 450 seats in the 6th State Duma, the lower house of the Federal Assembly (the legislature). United Russia won the elections with 49.32% of the vote, taking 238 seats or 52.88% of the Duma seats.

This result was down from 64.30% of the vote and 70% of the seats in the 2007 elections. The Communist Party of the Russian Federation received 19.19% of the vote and 92 seats, its best result since 1999, while A Just Russia received 13.24% and 64 seats, with the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia getting 56 seats with 11.67% of the vote. Yabloko, Patriots of Russia and Right Cause did not cross the 7% election threshold. The list of parties represented in the parliament did not change.

United Russia lost the two-thirds constitutional majority it had held prior to the election, but it still won a majority of seats in the Duma, even though it had slightly less than 50% of the popular vote. The Communist Party, Liberal Democratic Party and A Just Russia all gained new seats compared to the previous 2007 elections.

The election received various assessments from abroad: positive from the Commonwealth of Independent States observers, mixed from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and critical from some European Union representatives and the United States. Reports of election fraud and voter discontent with the current government led to major protests particularly in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. The government and United Russia were in their turn supported by rallies of the youth organizations Nashi and Young Guard of United Russia. Later, the actions of anti-government protesters sparked the fear of a colour revolution in Russian society, and a number of the "anti-Orange" protests were set up[2] (the name alludes to the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, the most widely known color revolution to Russians) including one on the Poklonnaya Hill in Moscow, the largest protest action of all the protests so far according to the police.[3][4][5]

The Central Electoral Commission issued a report on 3 February 2012, in which it said that it received a total of 1686 reports on irregularities, of which only 195 (11.5%) were confirmed true after investigation, a third (584) actually contained questions about the unclear points of electoral law, and only 60 complaints claimed falsifications of the elections results.[6] On 4 February 2012 the Investigation Committee of the Office of the Prosecutor General of the Russian Federation announced that the majority of videos allegedly showing falsifications at polling stations were falsified themselves.[7]

Statistical analysis of poll data have shown massive abnormalities that most researchers explain by mass-scale electoral fraud.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

- ^ "Russian political parties to kick off pre-election debates". RIA Novosti. 8 November 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Антиоранжевый митинг проходит на Поклонной горе RIAN (in Russian)

- ^ Путин: На митинге на Поклонной мог быть задействован адмресурс, но только на нем собрать так много людей невозможно (in Russian). Rosa village. Interfax. 4 February 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ Померились цифрами vz.ru (in Russian)

- ^ Как митинг на Поклонной собрал около 140 000 человек politonline.ru (in Russian)

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lenta-ninetywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ СКР объявил ролики с нарушениями на выборах смонтированными Lenta.ru (in Russian)

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

mathwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

cambridgewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

shpilkinwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Enikolopov, Ruben; Korovkin, Vasily; Petrova, Maria; Sonin, Konstantin; Zakharov, Alexei (8 January 2013). "Field experiment estimate of electoral fraud in Russian parliamentary elections". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (2): 448–452. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110..448E. doi:10.1073/pnas.1206770110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3545790. PMID 23267093.

- ^ Bader, Max; Ham, Carolien van (2015). "What explains regional variation in election fraud? Evidence from Russia: a research note" (PDF). Post-Soviet Affairs. 31 (6): 514–528. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2014.969023. ISSN 1060-586X. S2CID 154548875.

- ^ Moser, Robert G.; White, Allison C. (2017). "Does electoral fraud spread? The expansion of electoral manipulation in Russia". Post-Soviet Affairs. 33 (2): 85–99. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2016.1153884. ISSN 1060-586X. S2CID 54037737.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search